By Art Kabelowsky, DNR Outreach and Communications, Fitchburg;

Arthur.Kabelowsky@wisconsin.gov or 608-335-0167

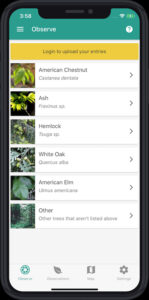

The main page of the TreeSnap app as seen on a mobile phone. / Photo Credit: TreeSnap.org

It takes more than a village to foster healthy forests. More than a township, a city and a county, too. Sometimes, even more than a state.

That’s why the Great Lakes Basin Forest Health Cooperative (GLB FHC) was formed four years ago by Holden Arboretum in Ohio and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service.

Geographically, the group’s region encompasses an area from New Jersey to Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is an active member.

The collaborative focuses on four species groups which have been ravaged by pests and diseases:

- Ash (emerald ash borer)

- Elm (Dutch elm disease)

- Beech (beech bark disease and beech leaf disease)

- Hemlock (hemlock woolly adelgid and elongate hemlock scale)

The goal of the GLB FHC is to locate pest- and disease-resistant trees of those species that can then be studied, tested and bred to improve overall survival chances for that species in that region.

In turn, the best way to do that is to enlist the public’s help. Yes, indeed: There’s an app for that.

With the availability of a TreeSnap app for phones and tablets, the GLB FHC has deployed an easy-to-use online tool to pinpoint pest- and disease-resistant ash, elm, beech and hemlock trees. Together, the public can provide the depth and breadth of information that covers villages, cities, counties and states all over the region.

“What’s really good about (the TreeSnap app) is that it can drive citizen science in a way that doesn’t demand so much technical expertise … (and doesn’t require) collecting leaves to take to the lab,” said Scott O’Donnell, forest geneticist and ecologist with the DNR.

“You can take a photo, answer some questions and tap your phone to get the information to us.”

Not only that, but the app potentially increases the number of people gathering information on resistant trees across the region a hundredfold. The app recently surpassed 20,000 submissions.

Scott O’Donnell, center, a forest geneticist with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Forest Economics and Ecology section, updates members of the DNR Forest Health team on upcoming genetic projects at an orchard near Lake Tomahawk in Hazelhurst during the Forest Health team’s summer meeting on May 25, 2024. / Photo Credit: Art Kabelowsky, Wisconsin DNR

O’Donnell said that if he went out on his own to look for resistant trees, “I could spend an entire year and get 10, maybe 15 candidate individuals.

“The more (citizen assistance) you have in any resistance trial, the better the chance of success you have” on the larger scale, O’Donnell said. “It’s like we’re looking for a silver bullet, but the more individuals you have in the trial, the better the chance you have to find potentially immune individual (trees) to work with.”

And because it’s an app for phones and tablets that are usually in a hiker’s pocket or backpack anyway, it reduces follow-up time for forest professionals.

“I’ve spent time looking for possible lingering trees, which I could have found more quickly if I had better information,” O’Donnell said. “This takes care of that… We can use the location to check the tree and then tell people, ‘That ash you’ve found might be the start of a completely new breeding program.’”

In many ways, O’Donnell’s main responsibilities involve orchard management and seed procurement. But he also “helps guide (DNR) decisions (by) advising the Forestry Division using genetic theory to make management decisions in reforestation, silviculture and studying seed sources so we do better with our choices of what to plant and where.

“Tree breeding is very expensive if you’re going to do it right,” O’Donnell said. “As a collaborative, you can dilute the up-front costs and the maintenance costs through working with other states and the federal government.

“With the number of mother trees you might collect seed from, the more hands you have, the better the work’s going to be.”

O’Donnell, like the GLB FHC, spends time studying the effects of climate change on forests throughout the state and region. He also serves as the outreach specialist for the DNR’s newly revitalized Tree Improvement Program, using genetics to build more resilient forests and to make sure DNR seedlings “provide stronger, straighter trees for the forest industry, private landowners and state parks and lands.”