By Brian Zweifel, DNR Forest Products Specialist, Brian.Zweifel@wisconsin.gov

What is Biochar?

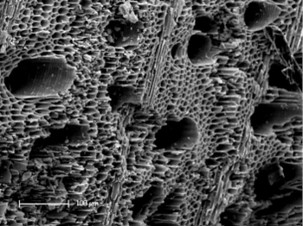

Microscopic structure of biochar. Photo credit: UK Biochar Research Centre

Biochar is basically just charcoal with a special mission, to be used in the soil. The US Biochar Initiative (USBI) defines it as “carbonized biomass obtained from sustainable sources and sequestered in soils to sustainably enhance their agricultural and environmental value under present and future management.”

Biomass, such as unmerchantable wood waste, is transformed into this carbon-rich material in a low oxygen environment, cooking most non-carbon materials out of it and leaving the material’s basic structure intact. This carbon skeleton is what gives biochar many of its desirable properties.

The former vessels and pores in the plant material are now able to adsorb nutrients and water before they can move below the rooting zone. This helps reduce nutrient leaching into groundwater and plant water stress by keeping them available in the rooting zone. This structure also has a high cation exchange capacity, making biochar very effective at binding pollutants like mercury and other heavy metals found in urban/industrial areas.

An added benefit of using biochar in degraded soils is that it is great at providing protected spaces for beneficial soil microbes. Fungal hyphae and bacteria readily colonize biochar particles, which provides protection from adverse conditions and helps improve soil health. Another very promising attribute of biochar that it is a very stable and long-lived form of soil carbon. Studies in the Amazon Basin have found evidence of charcoal (biochar) used by indigenous groups to improve the heavily leached soils that date back several hundred to thousands of years ago. The discovery of this “terra preta,” or literally “black soil” in Portuguese, was the spark that started researchers looking into the long-lived nature of biochar, its ability to improve soil health, and the possibility of using it to sequester carbon in soils for centuries. A wide variety of scientific trials are underway across the globe, including right here in Wisconsin.

Production Demonstration

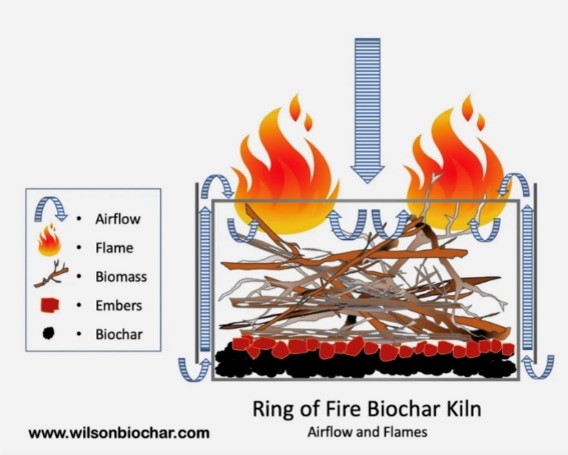

Flame-cap kiln design limits oxygen to efficiently produce biochar. Photo credit: Wilson Biochar, LLC.

During the summer of 2022, the Wisconsin DNR Forest Product Services program purchased two “Ring of Fire” biochar kilns produced by Wilson Biochar, LLC, and had them shipped to Wilson State Nursery in Boscobel, Wisconsin. These kilns were chosen because they are easily transported in sections and feature a double-walled flame-cap design, which offers higher biochar production efficiency and safety than open-pile burning. The two kilns were also able to be combined to make one larger-diameter kiln, allowing staff to test the use of a skid-steer for loading longer-length brush.

Once a mound of brush was added to the kiln, a small pile of tinder and paper scraps was placed at the top of the brush pile and ignited. The initial pile burned down quickly, and more brush was added each time the material burned down to coals. Adding fresh fuel each time the fire burns down consumes the available oxygen at the surface of the material and doesn’t allow the coals underneath to be turned to ash. This is where the term “flame-cap kiln” comes from.

The combination of the flame cap limiting oxygen to the coals and the heat retention of the double-wall design increases the efficiency of the kiln and the quality of the biochar. At the end of the day, water was used to put out the fire and cool things down. Quenching the fire right away keeps the remaining coals from being consumed and turned to ash, a crucial step to maximizing biochar yield.

Nursery Goals

Currently, the nursery relies on regionally harvested sedge peat to increase the soil organic matter in the seedling beds. Organic matter improves soil structure, which results in increased water infiltration following rains and increased water-holding capacity of the soil; it also enhances root growth into the more permeable soil and improves soil nutrient-holding capacity to inhibit those nutrients from leaching out of the seedling’s root zone. However, the cost of harvesting and transporting the sedge peat to the nursery is expensive, the practice is not sustainable, and the organic peat material readily breaks down in the soil and must be replenished regularly.

Biochar trials are being carried out at greenhouses and nurseries around the world that use peat products and other non-renewable media, like perlite or vermiculite, for containerized woody and herbaceous plant production. DNR nursery managers decided to test the effects of biochar at Wilson State Nursery because of the promising initial results of these other trials.

Biochar Charging

Although not employed in this trial, it is important to cover the topic of “charging” biochar, what it is, its benefits, and some common methods for increasing the potency of this wood-derived soil amendment. Common methods for charging biochar include incorporating it into compost or worm castings, soaking it in nutrient-rich compost tea or animal waste, or soaking it in commercially produced fertilizer solution, though this last option does not incorporate beneficial soil microbes like the previous methods.

Staff originally planned on charging the biochar by soaking it in a liquid fertilizer solution to let it absorb nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, but decided to forgo this recommended step to be consistent with similar trials underway by the US Forest Service. Raw biochar is like a dry sponge when placed in the soil, soaking up whatever nutrients may be available and can lead to initial reduced plant growth until the biochar reaches equilibrium with the surrounding soil. State nursery staff regularly fertilize seedling beds and can monitor for any growth deficiencies, adjusting fertilizer applications accordingly to make up for this effect.

Field Application

Biochar applied at Wilson State Nursery in Boscobel, WI. Following application, the biochar was rototilled into the test beds. Photo credit: Wisconsin DNR

In total, eight different species grown at the nursery were chosen, and biochar plot locations were randomized. Approximately 70 pounds of biochar were weighed-out for each plot, which equates to roughly three tons per acre. In urban tree plantings, the biochar could be spread by hand in the rooting zone during planting or via a drop spreader, or similar type of equipment that limits the amount of wind dispersion, for larger planting areas.

In the growing seasons to come, nursery staff and US Forest Service partners will monitor the effects the biochar has on soil health, look for any effects/interactions with chemicals used to control pathogens (including fungal fumigants), and quantify effects on seedling root and stem biomass.

Key Takeaways

The Wisconsin DNR Forest Products Services team was proud to assist with this project as part of our commitment to promote markets for wood residues, small-diameter trees, and underutilized species in Wisconsin. By promoting emerging markets and technologies like biochar, we aim to improve wood utilization and strengthen Wisconsin’s forest products industry. Our motto is “Healthy forests require healthy forest product markets.”

Lessons learned from this trial and others allow us to provide technical assistance to groups or businesses that wish to incorporate biochar production into habitat management work, wildfire fuels reduction projects, better utilization of wood waste, or as an additional revenue stream from woody biomass facility heat or power production.

Biochar is an emerging market that has a lot of hype around it, but there are many scientific studies underway to continue sifting and winnowing the many claims associated with biochar’s benefits. If the claims prove to be scientifically supported, biochar may someday be an established global market that benefits us all by removing harmful pollutants from soils and groundwater, reducing methane emissions and noxious odors from livestock production, improving soil health and fertility, reducing the amount of water needed to grow crops, and even reducing the risk of catastrophic wildfires.

As a final bonus, biochar is a long-lived carbon-rich material containing up to 80% carbon, which is locked away in the soil for hundreds of years or more. Even in this small trial, nearly one ton of carbon dioxide was averted from the atmosphere. Think of what global-scale production and application could do to reduce atmospheric levels of this major greenhouse gas.