By Art Kabelowsky, DNR Outreach and Communications, Fitchburg;

Arthur.Kabelowsky@wisconsin.gov; 608-335-0167

Over the night of July 19-20, 2019, Mother Nature carved a massive swath of destruction through northern Wisconsin.

Today, after years of hard work cleaning up after the massive derecho windstorm of ’19, local foresters, work crews and landowners have only begun to understand the breadth and depth of the damage as they process the lessons learned.

In many areas, the recovery work remains incomplete. Some of that forest damage will never receive direct attention.

While pine trees in the background seemed unaffected, other parts of a stand in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest were wiped out by the derecho that ravaged northeastern Wisconsin in June, 2019. / Photo Credit: John Lampereur, United States Forest Service

Overall, “150,000 acres of timberland was flattened overnight,” said Richard Lietz, who, at that time, was the Oconto Falls Team Leader for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Division of Forestry.

Lietz — now a supervisor for the DNR’s Peshtigo Area forestry team — was then in charge of staff in Oconto, Shawano and Menominee counties. “All of those were hit (by the derecho), but Oconto was hit the hardest,” he said.

The damage ran deeper than the millions of trees damaged in northern forests. The DNR estimated that at least some damage occurred over more than 250,000 acres in Wisconsin, including 14,577 acres of state land. More than half a million people lost power across Wisconsin and Michigan, some for up to a week. Trees fell on people camping in tents and recreational vehicles. Debris caused the deaths of horses and other animals. Fallen trees blocked driveways, roads and bridges, making it impossible for emergency vehicles to reach residents quickly.

“Loggers were challenged to absorb so much volume on the market in such a short period,” Lietz said. “Top that with a highly challenging wood market, to begin with, and it was amazing that the mills and markets were able to find ways to process such a large amount of volume.”

The derecho once was an anomaly in the world of extreme weather, rarer than both tornadoes and hurricanes, but is becoming more frequent due to the amount of energy and moisture that warmer air can contain.

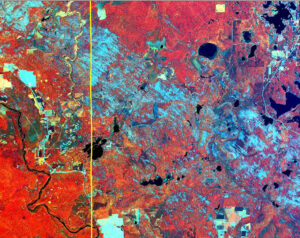

An infrared satellite photo of a portion of the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest shows damaged areas (in cyan) cutting a swath from the northwest corner of the photo to the southeast corner after the derecho storm of 2019. Red represents green, healthy forest; black represents water.

Named after a Spanish adjective meaning “straight line,” a derecho is an oversized, long-lasting, devastating wind event defined by the National Weather Service as “clusters of severe thunderstorms capable of producing winds … as high as 100 miles per hour or higher.”

To earn official classification as a derecho, a storm must (in part) cover 400 or more miles and produce frequent wind damage reports over a wide region. The Wisconsin derecho of 2019 met those criteria and then some.

“We had about 130,000 acres of damage” inside the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, said John Lampereur, a United States Forest Service silviculturist working on forest and ecosystem restoration projects in the Lakewood/Laona Ranger District (the southeasternmost corner of the forest).

That means about 8.5% of the forest’s 1.5 million non-contiguous acres sustained damage.

Lampereur told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in 2019 that some mounds of fallen trees were piled 15 feet high, and he said he told his wife that “this is going to change everything. We’re going to be working on this for 10 years.”

Asked about the five-year status of that comment, Lampereur said, “We easily have another five years of reforestation and timber stand improvement activities to go.”

He also was on the job in 2007 when a tornado struck the forest, damaging roughly 11,000 acres of national forest lands.

“Looking back, that was just a training exercise,” Lampereur said. “The path of the tornado was about 38 miles by a half-mile wide. (The derecho) was a lot longer — and it was six miles wide.”

“We had 12 to 13 times the damage (compared to the tornado), and we were talking about a lot of land in the first place.”

The cab of a pickup truck after it was smashed by a fallen tree during the 2019 derecho windstorm that ravaged forestland in Northeastern Wisconsin. The truck was found on Sawyer Lake Road in Oconto County. / Photo Credit: John Lampereur, United States Forest Service

Lietz — who drove through the derecho on his way to a weekend trip to his cottage — instead started a string of countless consecutive days of work.

“By the time I got there, my phone was blowing up with people telling me that thousands of trees were down, and major roads were closed,” said Lietz.

Although they had barely had time to think about it, area governmental leaders sprung into teamwork-based action.

A unified command center was formed in Oconto County, and DNR and USFS crews pitched in to help county and municipal crews clear main roads as quickly as possible. The USFS found a group of about 50 campers at Boot Lake Campground who could not get out. The USFS had to set up generators and restore a damaged radio tower to restore communications, and an informational webpage was set up.

“Once the emergency was taken care of, it was DNR’s job to handle landowner response,” said Lietz. “Not just MFL (Managed Forest Law) landowners, all forested landowners.”

“We put together a team comprised of DNR foresters, private foresters, Forest Health staff and loggers and held town hall meetings. The goal of the meetings was to provide basic information about working with loggers, what to expect, including example contracts, why you should work on soft woods first (because beetles will come after them) and what to do with blown-down wood that loggers aren’t interested in.”

Lietz recalled that over 19 established timber sales set up by the DNR were affected by the storm, necessitating contract amendments that changed the terms to salvage sales. Many trying to sell their timber found that prices had dropped by half or more.

Lampereur said one of the top priorities for the USFS was to remove trees on land adjacent to private property, especially if they had coniferous trees.

“That’s heavy fuel loading,” he said. “Any other areas away from private land that had a lot of conifers came next. We figured that was the stuff that was the most flammable and was going to rot first.”

While landowners quickly tried to sell or remove fallen timber, the USFS took a bit longer to get the ball rolling on its sales.

“Before you can move a stick, you have to have public input and analysis,” Lampereur said.

In hindsight, he said, the delay helped to bolster the price paid to private landowners.

The DNR conducted an aerial survey to improve patchwork satellite imagery and capture detailed mapping photographs of the damage. The DNR also created mapping layers and placed them in the Geographic Information System for comparison and analysis.

Lampereur said one of the lessons learned was to send the planes up more quickly to get a quick and accurate large-scale assessment. He said USFS also is working on public documents that would allow the agency to move more quickly with salvage sales after a weather event.

Lietz recalled that the various agencies discussed what did and didn’t work well in the days, weeks and months after the storm, including using social media and the My Wisconsin Woods program to quickly reach landowners and take their requests.

Of course, emotion played a significant role in the post-storm response with individual landowners involved.

“There’s definitely an emotional side to it,” said Lietz. “Where our foresters were impacted wasn’t so much the land they managed, but working with landowners who have had the land in their family for generations asking, ‘what do we do now?’ It really hurt.”

Five years after the event, Lietz and Lampereur believe their agencies have made substantial progress in handling all aspects of the aftermath.

“In retrospect, it was amazing that we got as much cleaned up as we did,” said Lampereur. “We had about 60,000 acres with damage of more than 50 percent. Most of it was sold within the first three years, although we still have sales open now. At first, we thought none of this could be sold after 18 months, but we still find salvageable, good-quality stuff.”

Lietz said the derecho will always be part of the DNR’s training for new staff.

“We tell them this was a storm for the century,” he said. “You’re always going to see the effects of this. Driving north on (State Hwy.) 32, you get to (State Hwy.) 64, and new people say, ‘Wow, there are a lot of new trees.’ But old-timers say, ‘Wow, where did all the trees go?'”

As Lampereur said: “We never thought we’d be able to sell as much of the wood as we were able to, or that we were able to clean up as much as well as we did.”

“It took a few years off everybody, though.”