A photo taken June 20, 2025, shows dead and dying oaks near Whitewater Lake in Walworth County, following a period of defoliation and summer drought. / Photo Credit: Wisconsin DNR

By Bill McNee, DNR Forest Health Specialist

Bill.McNee@wisconsin.gov or 920-360-0942

Property owners are encouraged to monitor their trees for signs of decline and mortality, as the last few years have been marked by drought and spongy moth defoliation.

Landowners who have oak, birch, crabapple, aspen, willow, tamarack and basswood (linden) trees should be particularly watchful, because the caterpillars of this invasive insect prefer these species. Many other tree species are not preferred by the caterpillars and are less likely to be heavily defoliated, but are more likely to die if heavy defoliation should happen.

This article focuses on oak impacts.

The 2021-24 spongy moth outbreak has now collapsed statewide; no defoliation has been observed as of late July 2025. Only a few reports of single caterpillars were received by Wisconsin DNR Forest Health staff. (Note: Parts of Wisconsin may be experiencing a continuing outbreak of different caterpillars known as “oak leafroller” and “larch casebearer.”)

Aerial surveys conducted in eastern Wisconsin found increased oak mortality compared to 2024. Aerial surveys are in progress in other parts of the state.

A mature spongy moth caterpillar at Potawatomi State Park in Door County on July 18, 2025. / Photo Credit: Wisconsin DNR

Host trees that were heavily defoliated or drought-stressed over the past few years have an increased risk of dying, especially if they were weakened by two consecutive years of heavy defoliation. Low-vigor oak trees are commonly attacked by Armillaria root disease fungi and the native beetle twolined chestnut borer. It is common for weakened, defoliated trees to remain alive for one to three years before finally dying.

A salvage harvest must be carefully timed so that most stand mortality has occurred, while also addressing the timelines of organizing a harvest and declining wood values. Consult a forester if a significant amount of tree decline, and/or mortality, is observed.

The condition of the tree crown prior to defoliation is the best (though still imperfect) indicator of tree survival following heavy defoliation. Oaks with good crowns — normal foliage and few dead branches in the upper crown — should have mortality rates below 10% during an outbreak, in the absence of other stresses such as drought.

In contrast, heavily defoliated oaks with poor crowns — more than 50% dead branches or dieback in the upper crown and small, thin foliage — can be expected to have high rates of mortality. Wildlife typically benefits from scattered tree mortality and small openings, but excessive mortality can affect a landowner’s management objectives.

The next few years can be a suitable time to conduct silvicultural activities in susceptible stands, as it is likely to be at least several years until the spongy moth population rebounds to high levels (depending on location and unknown future weather conditions).

The pest is continuing to slowly spread into western counties, and this period of low populations can be a window of opportunity to prepare western stands for the arrival of spongy moth. In particular, the Driftless Area and Northwest Sands are predicted to have intense and frequent outbreaks in the future.

First outbreaks of an invading pest are commonly the most severe and damaging, and landowners can often reduce impacts by preparing their stands ahead of time. Species diversification and increased stand vigor can also help to prepare a stand for additional future insect and disease arrivals, climatic conditions, etc.

Monitor spongy moth populations where management activities are planned within the next few years. Delaying a harvest until a predicted outbreak ends may be suitable, especially since the cost of an aerial spray to protect weakened trees generally costs $80-100 per acre.

Three current-year spongy moth egg masses on a tree in Walworth County in October 2021. / Photo Credit: Wisconsin DNR

In general, give weakened stands time to recover from the stress of defoliation or intensive management before subjecting those trees to additional stress. This typically means leaving at least one growing season between heavy defoliation and management activities (in either order) in healthy, vigorous stands. Leave at least two growing seasons in stands with lower vigor, as they will need more time to recover from a stress such as defoliation or drought. Monitor the stand for signs of decline and/or mortality during this period in case active management needs to be altered.

Spongy moth silviculture can be incorporated into stand management planning as one of the considerations. Strategies may include:

- Increasing the proportion of trees that are less desired by feeding caterpillars (such as pine, spruce, cherry and hickory).

- Reducing the proportion of trees that are preferred by the feeding caterpillars (such as oak).

- Increasing stand vigor through thinning and removal of host trees that are low vigor or suppressed.

- Favoring oak trees with smooth bark to force more spongy moth caterpillars to the ground, where they are more vulnerable to predation.

- Removing a mature oak overstory to release understory pines.

- Regenerating a stand while populations are low and stump sprouting potential is adequate (when applicable).

Passive (“hands-off”) management in oak stands that are highly susceptible to spongy moth defoliation tends to result in an acceleration of forest succession to shade-tolerant species such as maple. However, this approach also increases the risk of having an understocked stand, should heavy mortality occur. Dry sites may transition to a pine cover type if heavy oak mortality occurs. Over time, successional processes usually create a stand that is less susceptible to intense outbreaks of spongy moth, but management goals involving oak (e.g., economic value, acorn production) can be negatively impacted.

Looking at spongy moth egg mass numbers on a specific property is the best way to determine if there is a potential problem in the next growing season. The masses are tan-colored lumps about the size of a nickel or quarter. Egg masses are found on trees, buildings and other outdoor objects and may also be found inside protected places such as firewood piles and birdhouses. Egg masses produced in 2025 will feel firm and appear darker in color than older egg masses, which appear faded, feel spongy and do not contain viable eggs.

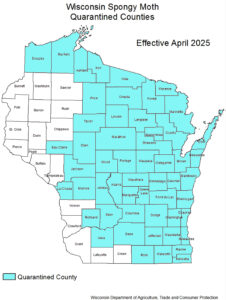

Spongy moth is considered generally established across the eastern two-thirds of Wisconsin. When spongy moth populations are high, they are most likely to be seen within parts of the quarantined area, but may be present in non-quarantined counties. La Crosse County was added to the quarantine area in April 2025.

A map of Wisconsin showing counties that have been quarantined for spongy moth, as of April 2025. / Map Credit: Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection

Additional Recommendations

Property owners are encouraged to examine their trees and take action if needed. Specifically:

- Visit the Spongy Moth Resource Centerfor management information relevant to both forest and ornamental trees.

- Consult a forester or arborist for additional management recommendations. A forester directory is available. When seeking an arborist for advice about ornamental trees, check both of these directories: Wisconsin Arborist Associationand International Society of Arboriculture.

- An aerial spray guide is available online for landowners or groups interested in organizing an aerial spray to protect high-value trees.