By Brian Cole, DNR Forest Products Specialist, Green Bay

Brian.Cole@wisconsin.gov

Coming from Maine, I found this hard to believe. Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) has been the “money tree” in Maine since colonial times, when the king’s broad arrow marked pine trees to be used as ship masts. White pine was once “king” here in Wisconsin, too. I do not see why it cannot be king again.

History Of White Pine In Wisconsin

A photo showing cut-over land on the road between Iron River, Michigan, and Tipler, Wisconsin. / Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Before Euro-American settlement, it is estimated that 30% of what we call the Northwoods was a pine forest. The majority of the Northwoods was comprised of hemlock, sugar maple and yellow birch, with white cedar, tamarack, and other conifers mixed in (Apps, 2020). Eastern white pine quickly became the tree of choice with loggers. One main reason was that white pine floats high, making it ideal for river drives. Secondly, white pines were some of the largest and tallest trees in the forest, with clear boles of 20 feet or more. It is estimated that there were 16-20 trees per acre with diameters at breast height (DBH) of 36 inches or larger (Apps, 2020). Builders loved white pine as well. It is said that white pine from the Lake States built the Midwest cities. These large trees produced clear, straight lumber. Knots were considered structurally unsound in the 19th century. The wood is soft but tough, and it is easy to work with hand tools, making it nearly perfect for framing lumber. It holds paint and glue well, making it a cabinetmaker and woodworker’s delight.

Wisconsin’s Lumber Era started in earnest in 1850 with the harvesting of the “big trees” first. In 1892, Wisconsin produced over 4 billion board feet of white pine lumber (Monk, Guries, & Marty, 1998). By 1900, the average DBH of white pine trees harvested was five inches (Apps, 2020). By 1920, white pine was almost wiped out in Wisconsin. The land was cutover. Slash fires and attempted farming helped expose the bare mineral soil. Pioneer species, primarily aspens (Populus spp.) and birch (Betula spp.), reestablished first across the Cutover. Estimates of aspen-birch forests in northern Wisconsin prior to Euro-American settlement range from 315,000 acres to over 650,000 acres (Apps, 2020). By 1936, aspen-birch stands covered 5.2 million acres throughout Wisconsin. At first, the aspens helped white pine regeneration by providing the low shade needed by white pine saplings. In conjunction with increased fire suppression, white pine reproduction was strong on many sites by the 1930s. Forest managers promoted white pine reforestation as part of diverse management goals throughout the 1930s and 1940s. However, as the aspens bloomed, so did the paper mills, which preferred aspen pulp. By the late 1940s, paper manufacturing was the third-largest industry in Wisconsin. Forest management shifted to promote aspen growth. Today, aspen-birch is the second most prevalent forest type in the Great Lakes states, approximately 26% of the timberland area.

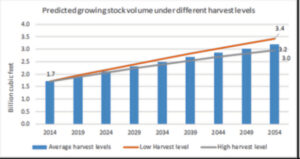

A chart showing predicted growing stock volume of white pine under different harvest levels in Wisconsin. / Graphic Credit: Wisconsin DNR

Eastern White Pine Silvics

White pine will grow almost anywhere throughout its range. However, it prefers well-drained sandy soils of low to medium site quality. On these sandy sites, white pine regenerates naturally, competes easily, and can be managed most effectively and economically.

White pine is intermediate in shade tolerance, and vegetative competition is a significant problem (Burns & Honkala, 1990). Although it will tolerate up to 80% shade, tree growth increases as shade is reduced. It can achieve maximum height growth in as little as 45% full sunlight. In competition with light-foliaged species such as the birches and pitch pine, white pine usually gains dominance in the stand. It can grow successfully in competition with black walnut. Against the stronger competition of species such as the aspens, oaks, and maples, however, white pine usually fails to gain a place in the upper canopy and eventually dies (Burns & Honkala, 1990).

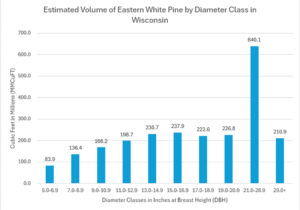

A chart showing eastern white pine volume by diameter class in Wisconsin. / Graphic Credit: Wisconsin DNR from 2024 FIA

Good seed years are thought to occur every 3 to 5 years, a few seeds being produced in most intervening years. Once established, White pine has excellent height and diameter growth. Annual volume growth remains high even in large (>24 in DBH), older trees. White pine responds well to management for reducing risks and increasing growth and value (Livingston, 2023).

Current Trends Of White Pine In Wisconsin

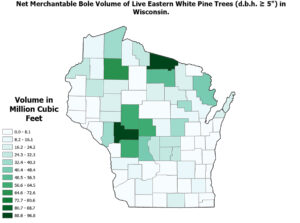

Today, eastern white pine is making a comeback. The growing stock volume is expected to continue increasing. The growth-to-removal ratio, an indication of utilization, is currently at 4.31 (2024 FIA Data). Suggesting that white pine is underutilized in Wisconsin. Two thousand twenty-four estimates of net merchantable bole wood volume of live trees (at least 5 inches diameter at breast height (DBH) in cubic feet on forest land is 1.28 billion cubic feet. Breaking that down by diameter class, the majority of the white pine is in the “sweet spot” for clear white pine of 21+ inches DBH.

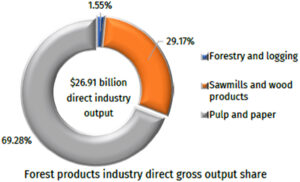

So why is white pine not being utilized? Silviculture in Wisconsin has been geared to promoting hardwood species. Makes sense: The pulp and paper industry is 60-70% of Wisconsin’s forest product industry. Hardwood pulp is preferred and more valuable. Hardwood lumber is also more valuable than softwood. So why should Wisconsin increase its white pine utilization? For several reasons. First, diversification. Not only is diversification good for the forest (as in bio-diversification), but it is also suitable for business. The forest products industry in Wisconsin is heavily weighted towards pulp and paper. Foreign competition, rising costs, and changes in consumer demand have put stress on companies.

A map showing net merchantable bole volume of live eastern white pine trees in Wisconsin by county. / Map Credit: Wisconsin DNR from 2024 FIA

The closure of the Verso mill in Wisconsin Rapids (July 2020) resulted in 900 employees being laid off (Mentzer, 2021). Continued shrinkage or worse, a total collapse of the pulp and paper industry (as happened in Maine) would be detrimental to Wisconsin’s economy. Secondly, tree pests and diseases continue to damage or kill valuable hardwood species. The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis), an invasive, wood-boring beetle that kills ash trees (Fraxinus spp.), has a projected mortality rate of 98%. Ash is used to make baseball bats, tool handles, furniture, and sports flooring.

Oak trees (Quercus spp.) are being affected by oak wilt, a deadly disease that kills thousands of oak trees each year. The fungus, Bretziella fagacearum, causes oak wilt. It is spread by sap-sucking beetles, delivering the oak wilt spores to fresh wounds. Once in an area, the disease spreads to nearby oak trees through interconnected (grafted) root systems, creating an expanding pocket of dead oak trees. The disease is a serious problem for species in the red oak group, such as northern red (Quercus rubra), northern pin (Quercus ellipsoidalis) and black oak (Quercus velutina).

A chart showing the Wisconsin forest product industry by percentage of output. / Graphic Credit: Wisconsin DNR

Once wilting symptoms are apparent on a red oak, the infected tree will lose most of its leaves and die within approximately one month. Among the white oak group, bur (Quercus macrocarpa) and swamp white oaks (Quercus bicolor) demonstrate moderate tolerance to the disease. White Oak (Quercus rubra) experiences even slower disease progression and may survive infection. Oak is used in flooring, furniture, interior trim, railroad ties, and barrel making.

A photo showing white pine weevil damage. / Photo Credit: Bradford Walker, Vermont Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation, Bugwood.org

White pine is not without its pests and diseases, most of which can be controlled through proper silviculture. The two most common that damage or kill white pines are the white pine weevil and white pine blister rust. The white pine weevil (Pissodes strobi) feeds on white pine as well as Norway spruce (Picea abies) and up to 20 other conifers (Livingston, et al., 2019). The white pine weevil kills the tops of conifers. Up to 2-3 years of growth may be destroyed (Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, 2008). After the leader is killed, lateral branches below the leader grow upwards. Multiple leaders compete to become the new leader, resulting in forked or multi-stemmed trees.

A “cabbage pine” showing the results of repeated attacks from the white pine weevil. / Photo Credit: treehelp.com

Repeated weevil attacks result in “cabbage pine” (Livingston, et al., 2019), a short, bushy tree resembling a cabbage. The white pine weevil is the most serious economic insect pest to white pine (Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, 2022). Weevil damage significantly reduces the value of white pine sawtimber.

An introduced fungus, Cronartium ribicola, causes white pine blister rust. The pathogen has a complicated life cycle alternating between currants or gooseberries (Ribes) and white pine trees(Livingston, et al., 2019). Infection on white pines causes stem cankers, which can girdle stems, leading to the death of branches, seedlings/saplings, and top kill. Ribes must be treated with herbicide within 1000 feet of white pine trees.

White Pine Silviculture

White pine silviculture begins with proper site selection. Deep, well-drained sandy sites without rooting barriers (plow pans, bedrock) reduce the incidence of hardwood competitors and future susceptibility to drought stress (Livingston, et al., 2019). Ribes control is essential to prevent white pine blister rust. Natural regeneration occurs best under an extended shelterwood regimen (Livingston W. H., Eastern White Pine Symposium: Management Trends, 2022). The first cut should be done in a good seed year, maintaining a 40-50% canopy closure. Scarify the forest floor to expose mineral soil and reduce competition.

White pine blister rust cankers releasing heavy resin. / Photo Credit: Ontario.ca

High-density seedling/sapling regeneration provides trainer trees to improve form and reduce browsing. Low shade reduces leader diameter and temperature of seedlings, resulting in lower white pine weevil infestation. Here in Wisconsin, patch cuts may be a better option. Mix eastern white pine in with hardwoods (Livingston W. H., Eastern White Pine Symposium: Management Trends, 2022). Use hardwood trees as trainers and for low shade. Keep high-density saplings to minimize weevil damage. Pine of the future will be grown in mixed species, irregular stands. Applying all the foregoing principles in the patches (Seymour, 2022).

After 15-20 years, remove the overstory. Prune branches on lower boles to avoid black knots. As the trees grow, spacing is more important than basal area per acre (Seymour, 2022). They need room to grow. At 20 feet tall, the trees require 12-15 feet spacing with 200-300 trees per acre (TPA). At 40 feet tall, the trees require 20 feet of spacing (100-120 TPA). At 60-70 TPA, the trees require 60 feet of spacing. At 30-40 TPA, the trees require 80 feet of spacing. Start regenerating the next stand at this point. The final goal is trees that are 26-28 inches in DBH and 100 feet tall, with approximately 30 trees per acre worth $500-$1000 each (Livingston W. H., Eastern White Pine Symposium: Management Trends, 2022).

For all the details on white pine silviculture, please refer to Wisconsin Silviculture Guide DNR PUB-FR-805 2020, and Eastern White Pine Management Institute Symposium and Resources.

Conclusion/Discussion

White pine regeneration in Old Town, Maine. / Photo Credit: Wisconsin DNR

Like hardwoods, pine is most valuable when it is tall, straight, and clear. With proper silviculture and time, Wisconsin can once again grow big, clear white pine. Further diversifying our forest product industry. But is it as simple as, if the foresters grow it, the sawmills will cut it? Not exactly. Are Wisconsin sawmills set up for large-diameter white pine logs? Some are, most are not. Is there a market for white pine in Wisconsin and the Great Lakes region? Yes, but it could use some support and development. White pine is used in countless value-added products, boards, moldings, door and window jambs, exterior siding, interior paneling, and a host of other millwork and furniture items. It is just a matter of identifying and developing the primary and secondary manufacturers. After all, healthy markets equal healthy forests.

Works Cited

Apps, J. w. (2020). When the White Pine was King: a history of lumberjacks, log drives, and sawdust cities in Wisconsin. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Burns, R. M., & Honkala, B. H. (1990). Silvics of North America: Volume 1. Conifers. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service, Agricultural Handbook 654.

Livingston, W. H. (2022). Eastern White Pine Symposium: Management Trends. Eastern White Pine Management Institute Symposium Presentations. Retrieved from extension.unh.edu/eastern-white-pine-management-institute-symposium-presentations

Livingston, W. H. (2022). Updates on Insect Pests of Eastern White Pine. Eastern White Pine Management Institute Symposium Presentations. Retrieved from extension.unh.edu/eastern-white-pine-management-institute-symposium-presentations

Livingston, W. H. (2023, February 6). S.4 Ep. 1: The King’s Pine. SilviCast. (G. Edge, B. Hutnik, Interviewers, & J. Rogers, Editor) Produced by the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point’s Wisconsin Forestry Center. Retrieved from uwsp.edu/wfc/wisconsin-forestry-center/silvicast/season-4/the-kings-pine/

Livingston, W. H., Munck, I., Lombard, K., Weimer, J., Bergdahl, A., Kenefic, L. S., . . . Seymour, R. S. (2019). Field Manual for Managing Eastern White Pine Health in New England. Orono: University of Maine, Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station.

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry. (2008, April). White Pine Weevil. Retrieved from Forest Health and Monitoring, Maine Forest Service: maine.gov/dacf/mfs/forest_health/insects/white_pine_weevil.htm

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry. (2022). White Pine Weevil—Pissodes strobi. Retrieved from Got Pests?: maine.gov/dacf/php/gotpests/bugs/white-pine-weevil.htm

Mentzer, R. (2021, May 17). Sale Of Duluth Mill Points To Paper Industry Trends. Retrieved from Wisconsin Public Radio: wpr.org/economy/sale-duluth-mill-points-paper-industry-trends

Mladenoff, D. (2015, October 8). The State of Wisconsin’s Forests. University Place – Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters. Madison, WI, USA. Retrieved from youtube.com/watch?v=pDj2ejl4cYU

Monk, A., Guries, R., & Marty, T. (1998, October). Planting Southern Appalachian White Pine In Wisconsin: The Pros and Cons. Madison: University of Wisconsin Dept. of Forest Ecology and Management.

Seymour, B. (2022). White Pine Management in Maine. Eastern White Pine Management Institute Symposium Presentations. Retrieved from extension.unh.edu/eastern-white-pine-management-institute-symposium-presentations

Steen-Adams, M. M., Langston, N., & Mladenoff, D. J. (2007, July). White Pine in the Northern Forests: An Ecological and Management History of White Pine on the Bad River Reservation of Wisconsin. Environmental History, 614-648. doi:10.1093/envhis/12.3.614