By Elton Rogers, DNR Urban Forestry Coordinator; Elton.Rogers@wisconsin.gov or 414-294-8675 and Dan Buckler, DNR Urban Forest Assessment Specialist; Daniel.Buckler@wisconsin.gov or 608-445-4578

Veteran trees, also known by some as heritage trees, loom large in our imagination. If you have an image of a large, gnarly oak in your head, you’re on the right track. These are the trees that, according to the International Society of Arboriculture, are of exceptional cultural, landscape or nature conservation value. They are vitally important and deserve management attention to keep them on the landscape whenever practical.

In general, veteran trees are post-maturity and chronologically older than the rest of their species’ population in a given region or landscape. As a tree ages, it is subjected to multiple rounds of primary environmental stressors (drought, flooding, cold, heat, etc.) and secondary infestations (pests, diseases). Over time, the tree becomes less efficient at transpiring water, photosynthesizing sugars, translocating and storing those sugars and performing respiration. All of this leads to increased epicormic shoot growth (water sprouts), cavities, cankers, deadwood, hollows and more.

Arborists perform proper retrenchment pruning by removing only hazardous deadwood on a veteran bur oak in Washington Park (Milwaukee). Notice the dieback on the exterior of the crown and the epicormic shoot growth on the interior branches.

Benefits Of Veteran Trees

As humans, we glean wisdom and values from our elders. Veteran trees play a similar role to the other plants and organisms in the ecosystems in which they exist, as they are more likely to develop symbiotic relationships. Beneficial saprophytic fungi and saproxylic invertebrates (organisms that feed on dead tissue) thrive on veteran trees. Due to their large presence of dead wood, veteran trees provide a food source and habitat for these organisms that are otherwise not present in most manicured landscapes that arborists and urban foresters work in. The presence of mycorrhizal fungi increases water and nutrient uptake for both the veteran tree and potentially the other trees and plants in the surrounding landscape. The typically thicker and distorted bark of veteran trees provide habitat for lichen. Cavities and hollows present in many veteran trees provide habitat for birds, bats and other larger organisms.

There are also many human cultural values associated with veteran and heritage trees. In the 2013 book “Ancient And Other Veteran Trees: Further Guidance On Management,” Lonsdale eloquently summarizes: “Ancient trees link us culturally and historically to past generations of people who lived among them.” This is in addition to the more frequently discussed benefits, such as carbon sequestration, cooling, storm water retention and increasing air quality.

Challenges With Veteran Trees

Urbanization has necessitated the need for tree management, and veteran trees can pose several problems in the urban and suburban environment that their younger or rural counterparts do not. Veteran trees are more likely to shed large, dead wood from higher heights and more frequently than other trees. Due to the large presence of saprophytic fungi, it is also more likely for veteran trees to develop decay in the non-conducting xylem. This leads to hollows and cavities, which can lead to higher risk and liability associated with these trees and may require more frequent tree risk assessments and mitigation techniques. As a tree reaches veteran status, the maintenance and risk associated with these trees may begin to outweigh some of their measurable benefits.

How Can You Manage Veteran Trees In Your Urban Forest?

As a veteran tree begins to shed large dead branches and develop cavities and hollows, the frequency of risk assessments of the tree may need to be increased. Otherwise, the risk of personal injury and property damage will most likely increase over time. To reduce risk, veteran trees deemed hazardous should be pruned by a certified arborist to remove dead and senescing branches on the exterior of the crown. This process mimics the natural retrenchment process (Figure 1) but expedites it to prevent branches from falling and impacting targets beneath the canopy. The pruning clause of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) A300 should be consulted when arborists are managing veteran trees.

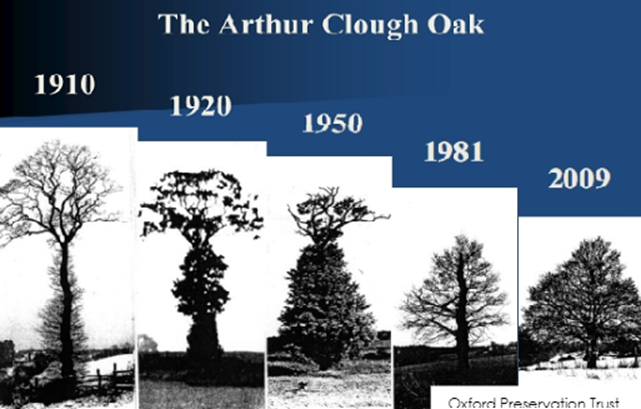

Figure 1: “The Arthur Clough Oak, shown as a sequence of photographs over a century, demonstrates survival strategies and potential for crown retrenchment. The first image shows the growth of the new lower branches after traditional management by shredding. Later, as the top of the crown died back, the lower branches formed a secondary lower crown.” (Fay, 2011). Image courtesy of Philip Stewart, Boars Hill.

When possible, any live crown removal/pruning should be completely avoided when working with veteran trees. As evidenced in a 2007 published paper, in most cases you should not remove epicormic sprouts on veteran trees as these could be playing a crucial role in prolonging branch and tree life. If inspection of a veteran tree reveals a risk rating above the tree manager’s tolerance, cabling and bracing and other tree support systems should be considered as viable mitigation techniques. Arborists should consult the supplemental support systems clause of the ANSI A300. Hollows and decay may limit previously viable cabling and bracing methods.

Veteran trees may also benefit from root excavation practices and potential soil amendment options to both detect root and soil quality issues and to also fix those issues. Finally, many veteran trees need protection from construction damage and development. On a large scale, this can be accomplished via tree ordinances, and on the landscape scale, tree protection zones, critical root zones and root protection zones should be established prior to construction to avoid increasing environmental stressors such as soil compaction.

Final Thoughts

Our understanding of veteran trees is evolving quickly, and we now understand more about their physiology and how it differs from younger trees. We need to continue to work to understand how to properly manage these veteran trees to optimize their health and longevity when practical. Only then can we maximize their ecosystem services and truly appreciate the historical and cultural significance of these mature trees. In the urban forestry profession, more attention is being paid to veteran tree management, and this will lead to greater age diversity, better risk assessment practices and an increase in practitioners’ knowledge of trees.