By Elton Rogers, Milwaukee Area Technical College and Dan Buckler, DNR Urban Forest Assessment Specialist, Milwaukee, Daniel.Buckler@wisconsin.gov or 608-445-4578

An urban forest is not an island. Trees and maintenance practices in one community inevitably affect the environment in another, while pests, pathogens and other damage agents don’t respect political boundaries. Because of these shared experiences, researchers have partnered with the Wisconsin DNR to assess the current state of publicly managed trees across the Milwaukee Metropolitan Area. Inventories from 40 organizations (mostly municipalities) totaling almost 440,000 trees point to worrying diversity issues and vulnerability to climate change, but also positive planting trends.

An article in the September issue of Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, the research publication of the International Society of Arboriculture, reviews the Milwaukee area’s species diversity, resilience to climate projections, availability of planting sites and more. A high-level summary of those results is below.

The Good

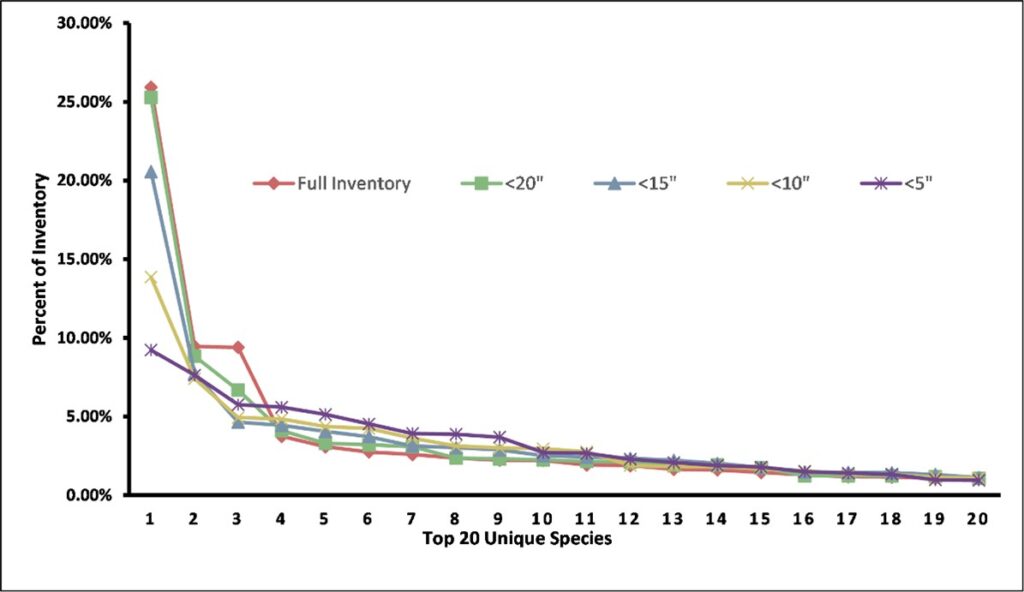

A positive result from the research was that urban forest managers and practitioners in southeast Wisconsin seem to be diversifying their tree plantings. Using diameter as a proxy for age, more recently planted trees are significantly more diversified than older trees (Figure 1). Lessons learned from past monocultural planting practices and subsequent invasive species events such as emerald ash borer and Dutch elm disease appear to have had a lasting impact on urban forestry practices. Future research will hopefully be able to rely on planting year data rather than diameter to gauge diversity-age relationships more accurately. Having a more diverse urban tree canopy will result in less vulnerability to future disturbances such as pest and disease outbreaks. This in turn leads to less maintenance costs, higher percentages of tree canopy cover, increased ecosystem services and overall more livable cities.

Figure 1. Five different diameter classes are overlaid to show the differences in tree diversity.

The Bad

Although the diversification of tree species helps to mitigate massive losses of a single species to an invasive pest, such as we saw with green ash and American elm in the past, it does not necessarily limit future losses to projected increases in annual temperatures and harsh urban growing conditions. The research revealed that if we are able to curb greenhouse gas emissions through the end of the century, the vast majority of the trees (398,176) would be considered low-moderate to low in terms of vulnerability to climate projections. However, if emissions continue to increase, potentially 244,273 trees (about 55% of the total inventory) would be considered moderately to highly vulnerable. Lessons from the past show that this would equate to millions (potentially billions) of dollars in lost ecosystem services and associated maintenance costs.

The Ugly

The research did reveal a lack of standardization within our tree inventory collection practices, which inhibits the efficiency and effectiveness of regional tree inventory analysis. While some of this is expected and often encouraged (a community’s inventory should reflect their unique situation), there are a handful of data fields which all inventories should have, including species, diameter, location, condition, the inventory year and the year planted, if known. In fact, these attributes are required by the DNR for entities receiving urban forestry grants.

What’s Next?

Urban trees in southeast Wisconsin are both vulnerable to urban stressors and increased annual temperatures and possess the ability to help combat these phenomena. Practitioners should continue to diversify their tree plantings and maximize canopy cover within their communities. Practitioners can also use this study and similar ones to help guide tree species selection and drive nursery stock availability. Communities should also work to maintain minimum inventory attributes and collect additional data useful for local management.