Rose chafers and Japanese beetles are starting to cause problems in some areas this summer. So far reports and damage are generally light for Japanese beetles, but in some areas rose chafer defoliation is noticeable.

Rose chafers are beetles that can defoliate many plant species. They have fairly long legs, and are a dusty mustard color.

Rose chafer defoliation was reported from Florence, Marinette, Oconto, Vilas, and Waupaca counties this year. Rose chafers are more common in areas with sandy soil where they will lay their eggs. The eggs hatch into white grubs which live in the soil and feed on grass and weed roots. My books inform me that birds can die if they eat adult rose chafers because of a poison in the beetles that affects the heart of small, warm-blooded animals. For information on rose chafer control, check out UW Extension publication A3122.

The last significant defoliation that I noted from rose chafer was in 2012, and before that it was 2005. These beetles feed on a wide variety of plants and prefer blossoms, but they will skeletonize leaves as well. Control is difficult because the adults are good fliers and can easily fly in from neighboring areas to re-infest your freshly sprayed plants.

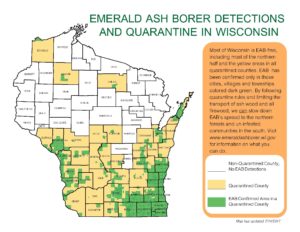

Japanese beetle populations will emerge in southern Wisconsin first, typically by the first part of July. Some areas of the state have building populations while others, like the Madison area, may have populations that exploded in the past and are more stable now. These insects are occasionally mistaken for EAB because they have some metallic green coloring near their heads. More commonly people will refer to the multicolored Asian ladybeetles as Japanese beetles, but the ladybugs are ladybugs and Japanese beetles are scarab beetles.

Japanese beetle adults feed on the flowers and leaves of over 300 plant species, including trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants. They can cause significant defoliation. The larval stage of Japanese beetle is a white grub that lives in the soil and feeds on plant roots. University of Wisconsin Extension has a Japanese beetle webpage including information on the damage caused by the adults, the damage caused by the white grubs, and control measures that are useful on the adults and the larvae.

Written by: Linda Williams, forest health specialist, Woodruff, (Linda.Williams@wisconsin.gov), 715-356-5211 x232.