By Olivia Witthun, DNR Urban Forestry Coordinator in Plymouth, olivia.witthun@wisconsin.gov or 414-750-8744

Laura Buntrock, DNR Urban Forestry Partnership and Policy Specialist in Rhinelander, laura.buntrock@wisconsin.gov or 608-294-0253

Dan Buckler, DNR Urban Forest Assessment Specialist in Madison, daniel.buckler@wisconsin.gov or 608-445-4578

Ram Dahal, DNR Forest Economist in Madison, ram.dahal@wisconsin.gov or 715-225-3892

We know that urban forests are a vital component of our economy and environment, making significant financial contributions to local, state and national economies, as well as providing critical ecosystem services. But until recently, the economic contribution of urban forestry has typically been aggregated into the broader green industry.

Background On The Study

In the Urban Forestry Economic Study, a ground-breaking study led by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and funded through a U.S. Department of Agriculture Landscape Scale Restoration grant, a comprehensive analysis of the economic contributions of urban and community forestry was completed across the Northeast-Midwest region, which includes 20 states and Washington, D.C. (Figure 1). This analysis includes economic impact numbers, employment numbers, industry outlook and a resource valuation.

Figure 1. Map depicting the 21 states involved in the survey.

The final products include regional, state and methodology reports. The regional report includes all 20 states of the Northeast-Midwest region, along with Washington, D.C., with 16 individual state-level reports, one for each state that signed on as a partner in the study. The methodology report will help with future replication of the study, allowing for tracking urban forestry economic contribution trends over time. Find factsheets for the regional and state reports on the Northeast-Midwest State Foresters Alliance (NMSFA) website.

For this study, urban forestry is defined as the establishment, conservation, protection and maintenance of trees in cities, suburbs and other developed areas. The scope of the urban forestry industry includes:

- Private businesses

- Utility companies

- Local and state governments

- Higher education institutions

- Nonprofit organizations associated with urban forestry in the region

Within the private sector, six industries were identified as being involved in urban forestry (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Scope of urban forestry in Northeast-Midwest region

To separate urban forestry from the broader green industries amongst private businesses and capture the involvement of other groups’ urban forestry activities, a survey was developed and distributed to individual contacts associated with any of the groups mentioned above. The survey data was then used to develop a complete profile of employment statistics associated with urban forestry businesses and activities. The profile statistics were then entered into IMPLAN software, an input-output regional economic modeling system, to estimate economy-wide ripple effects in the state economies stemming from direct economic activities in urban forestry-related industries. Find a full description of the methods in the methodology report on the NMSFA website.

Wisconsin’s Results

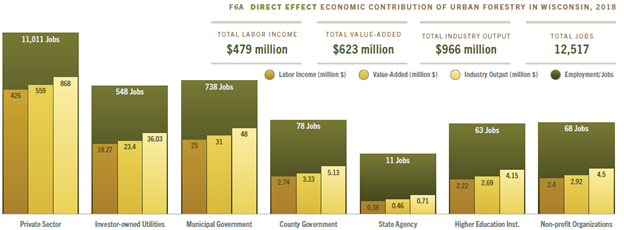

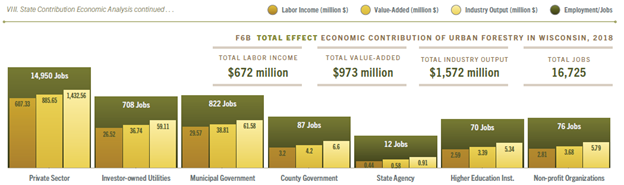

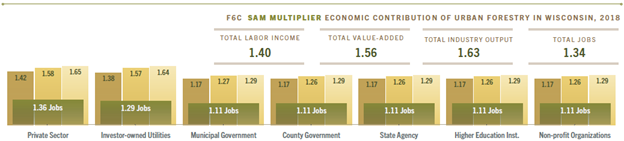

Results from the input-output modeling suggest that in 2018, urban forestry activities in Wisconsin directly contributed $966 million in industry output by supporting 12,517 full- and part-time jobs in various businesses and activities. Including direct, indirect and induced effects, urban forestry had a total contribution of $1.6 billion in industry output to the state economy, employing 16,725 people with a payroll of about $672 million (Figure 3). Every dollar generated in urban forestry contributed an additional $0.63 to the state’s economy.

Figure 3. Economic contribution of urban forestry in Wisconsin, 2018.

The report also found that Wisconsin’s urban forestry makes substantial contributions to local, state and federal taxes. In 2018, urban forestry businesses and employees in the state paid over $41 million in state and local taxes and about $96 million in federal taxes. Employee compensation and households were the largest categories, contributing to about 90% of federal taxes collected directly from urban forestry businesses and employees. Most of the state and local taxes were collected on the production and imports of goods, followed by household taxes.

The private sector represents about 88% of the state’s direct jobs (over 11,000) and industry output ($868 million). Public agencies (municipal, county and state) collectively contributed about $69 million in total industry output by supporting 921 jobs in the state’s economy. Higher education institutions and nonprofit organizations had total job contributions of 70 and 76, respectively. Every 100 jobs in urban forestry in Wisconsin resulted in another 34 jobs in other sectors of the economy.

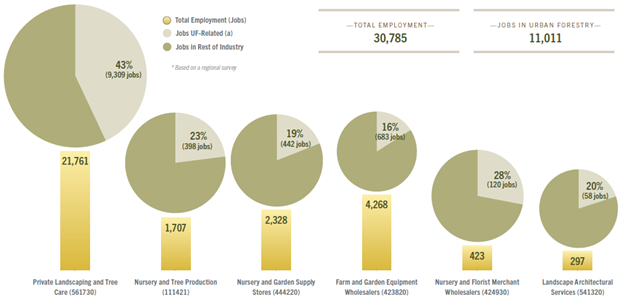

Survey results provide a more in-depth look at employment numbers for the private sector. Forty-three percent of private landscaping and tree care employees work in urban forestry, accounting for 9,309 jobs, whereas landscape architectural services reported the lowest employment numbers with 58 total jobs. Approximately one-quarter of nursery and florist merchant wholesalers (28.4%) and nursery and tree production employees (23.3%) perform work in urban forestry-related activities. Less than 20% of employees in the following business types perform work in urban forestry: landscape architectural services (19.6%); nursery and garden supply stores (19%); and farm and garden equipment wholesalers (16%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Average employment in private businesses in Wisconsin.

Looking Forward In Urban Forestry

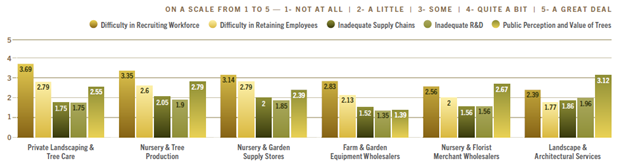

The future outlook of urban forestry is reported on a regional level by NMSFA. All sectors (private, government, nonprofit organizations, higher education institutions and investor-owned utilities) rated the future outlook of urban forestry between neutral and somewhat good. Only the nursery and florists’ supplies merchant wholesalers in the private sector reported an outlook slightly under neutral. In terms of issues influencing outlook, respondents from the following sectors said they had some or quite a bit of an issue recruiting for their workforce, impacting their urban forestry activities:

- Landscape and tree care services

- Nursery, greenhouse and tree production

- Nursery and garden supply stores

- Investor-owned utilities

Further, nursery, greenhouse and tree production and nursery and garden supplies stores rated inadequate supply chains as at least some of an issue that impacts their urban forestry activities.

Results differed on whether public perception and the value of trees impacted a business type’s urban forestry activities. Most private business types rated public perception and value of trees as between a little or some of an issue. In contrast, state agencies said public perception and value of trees was some and quite a bit of an issue impacting their activities (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Average severity of issues impacting urban forestry activities by business type (1 – not at all, 2 – a little, 3 – some, 4 – quite a bit, and 5 – a great deal).

The urban forestry industry is not only an economic driver, but trees themselves offer many economic benefits to our communities. It is estimated that trees cover almost 30% of Wisconsin’s urban areas, saving those areas and the 70% of the state’s population who live there $392.2 million a year across four broad categories of ecosystem services. These savings include $111.3 million from removing air pollutants, $54.9 million from stormwater reduction, $85.3 million from carbon sequestration, $74.4 million in electricity usage and $66.4 million in fuel usage avoidance. Additionally, urban trees were found to have an estimated compensatory value of $32.2 billion, reflecting the trees’ value as structural assets. These ecosystem services were calculated using the i-Tree Landscape methodology and informed by plot data collected from the statewide Urban Forest Inventory and Analysis program.

The comprehensive nature of this study leads to a complete picture of urban forestry contributions, including efforts of private businesses, public agencies and nonprofit organizations, as well as the ecosystem services of the trees themselves. It communicates the industry’s monetary benefits in terms of dollar values and jobs to lawmakers. These findings have significant management and policy implications and provide justification for the enhancement of current programs and the creation of new measures to support urban forest management.