Photo Credit: Delisa White

By Elton Rogers, Urban Forestry Coordinator

The DNR was recently contacted by a local news station to comment on a theory that tends to pop up alongside the tulips every spring: “botanical sexism,” a theory attributed to horticulturist Tom Ogren.

As a theory, botanical sexism is rather simple. It states that over time, humans have preferentially propagated and planted male trees, thus leading to increases in pollen production and subsequent allergens in our cities. The hypothesis is simple, and the term is catchy, so it is no surprise that it has made its way into the world of social media, having gone viral on several platforms over the last few years. The question remains, however, whether this concept is indeed factual.

Like most things in nature, the truth is often much more nuanced than it may first appear. To try and get to the bottom of this debate, we must first understand some basic morphology of tree reproduction. In general, we can lump tree reproduction strategies into three buckets.

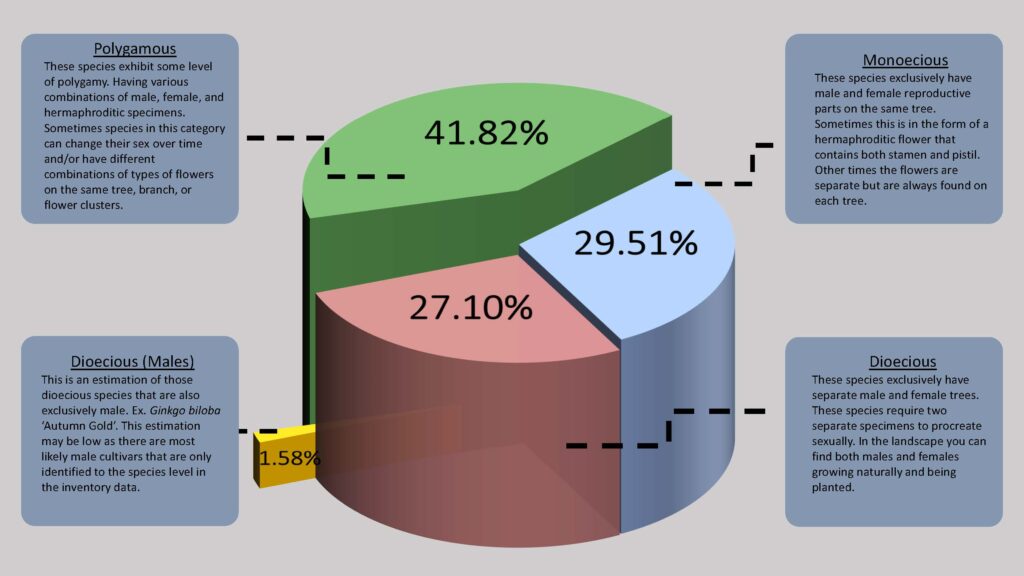

The first is those trees that have male and female reproductive parts on the same tree, whether within the same flower structure (hermaphroditic) or separate flowers. We’ll use the more general definition here and call all these trees monoecious. Conversely, you have trees that have male and female flowers on different trees, and this is known as dioecious.

Finally, there are a plethora of other reproductive strategies involving different combinations of polygamodioecious, polygamomonoecious, gynodioecious, etc. We will just call this third bucket polygamous, or in other words, it’s complicated. The number of trees that fall within each of these buckets will vary by geography. Figure 1 shows an estimate of the percentage of trees within each bucket for the roughly 200,000 street trees in Milwaukee.

Figure 1

Knowing that there is a limited amount of truly dioecious species can help shape the overall picture of the concept of preferential male propagation. Now, that is not to say we have not been doing this as an industry to an extent. There are several examples of dioecious species that have male-only cultivars. Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus), corktree (Phellodendron spp.) and ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) are just a few examples of species with male cultivars. Some of the reasons for this include decreasing seed production and decreasing the invasive potential of some species. It is worth noting that there are also female cultivars of various species and some cultivars that are neither male nor female. There are plenty of examples such as various freeman maple cultivars that were thought to be male cultivars that then subsequently produced female flowers and seeds in the landscape.

Now that we have some basic biology let’s look at the most recent research on the topic and try to draw some general conclusions. Researchers in New York found that when measuring pollen counts and tracing them back to the species of trees, 71% of all the airborne pollen came from just four genera of trees. Three of these are considered monoecious, and the fourth is a dioecious genera that is not actively planted in the landscape (Morus spp.) nor cultivated for male clones. Thus concluding that botanical sexism does not apply to New York City.

Given the similarities in the trees found in New York City to our trees here in southeastern Wisconsin, at this time, we would conclude that the theory does not apply to us as well, at least at a city or regional scale. Also important to recognize is that male versus female is not the only factor influencing allergen potential. Pollination strategies, species, age, climate, flowering time and more will all influence a given specimen’s allergen production. Urban forestry professionals need to factor in the disservices of trees, such as pollen and allergen production, during species and site selection.

However, now is a good time to remind everyone of all the ecosystem services that trees provide and understand that the benefits of a properly managed urban forest far outweigh any disservices. Continuing to select a diverse group of species and planting them in the proper sites is what is most important, even if you do choose to sprinkle in some male-only cultivars. This will help to ensure we maintain a healthy and resilient urban forest.