By Linda Williams, forest health specialist, Woodruff, Linda.Williams@wisconsin.gov, 920-360-0665

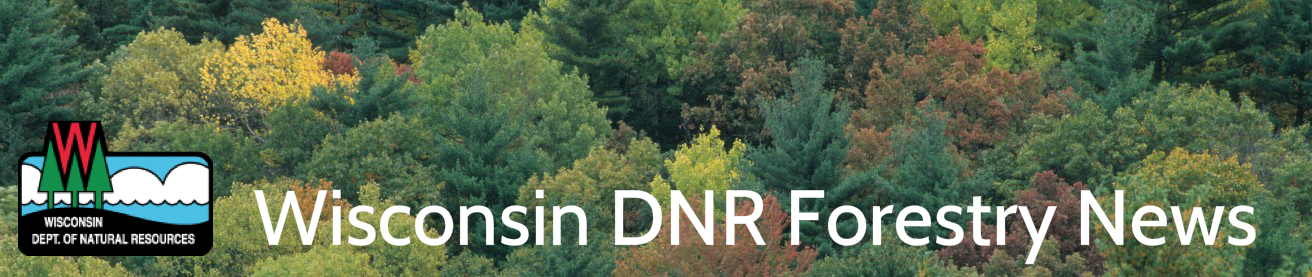

There are three things you may find interesting about gall rusts on jack pine at this time of year. The first is that as winter recedes, closer examination of the galls on jack pine shows that squirrels like to chew on them. The squirrels seem to prefer the smaller galls, with most chewing marks being observed on galls less than 2” in diameter. They eat the galls by scraping off the outer layers, leaving behind telltale teeth marks.

Squirrels sometimes feed on galls, scraping away the outer layers and leaving teeth marks behind.

Another thing you might notice about galls is that when there are heavy snow loads on trees in winter, branches and main stems may be prone to failure at gall sites. Having a gall does not guarantee that a branch or main stem will break, but it can create a weak spot that is more likely to break when placed under additional pressure.

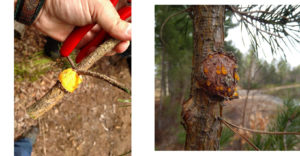

The third thing to notice in early spring is that the galls will start to turn bright orange/yellow as the fungus begins producing powdery spores called aeciospores. There are two different fungi that produce galls on jack pine in Wisconsin: eastern gall rust (pine-oak gall rust) or western gall rust (pine-pine gall rust). They both produce powdery aeciospores and are perennial, meaning they produce these spores every year in the spring.

Orange/yellow powder on gall surface (left) indicates that the fungus is producing spores. This happens once per year in spring. Before the spore-producing stage, you may see liquid drops oozing from the gall (right). This is a different type of spore type called pycnidia.

Most of the gall rusts in Wisconsin are thought to be the oak-pine type, or eastern gall rust (Cronartium quercuum). This rust fungus requires two hosts, oak and pine, to complete its life cycle. In Wisconsin, jack pine is the most commonly affected native pine species, but galls are found on planted Scotch pine as well. Other hosts of eastern gall rust include Austrian and red pine, although these seem to be less frequently impacted in Wisconsin.

There are a few areas in the state where western gall rust, or pine-pine gall rust (Peridermium harknessii), is prevalent. The galls of this rust look identical to those of pine-oak gall rust, but western gall rust does not require an alternate host. Instead, this gall rust produces orange powdery aeciospores in the spring which can directly re-infect pine if the conditions are right. In comparison, the aeciospores produced on pine by pine-oak gall rust must infect an oak leaf and produce a different type of spore before returning to infect pine. Damage to oak leaves is typically not enough to be noticed by the casual observer. There is no way to differentiate the two gall rusts without using a microscope to examine the length of the germ tubes.

Management and prevention of gall rusts can be challenging. The USDA Forest Service guidance indicates that for nursery operations, removing the alternate host (oak) within a ½ mile can help limit infection by pine-oak gall rust, while the Christmas Tree Pest Manual recommends removing all oaks within ¼ mile of Scotch or jack pine plantations. Management in forest stands is not easy or practical so getting healthy seedlings to start a new forest stand is important.

At the time of planting, don’t plant any seedlings that have galls on the main stem. Planting infected seedlings can often lead to mortality within four years. Many nurseries screen for this disease and use fungicides to prevent infection in nursery stock. If infection rates are too high, an entire cohort of seedlings may be culled.

Seedlings with galls should be culled at planting time.

Each year the Wisconsin DNR Forest Health team samples seedlings from the DNR nursery to check infection levels and reports the results in the Forest Health Annual Reports. The 2019 Annual Report is available on the DNR Forest Health Webpage or directly via this link. Reports from previous years can also be requested by emailing your local forest health specialist.