By Jodie Ellis, DNR Forest Health Team, communications specialist (Madison), Jodie.Ellis@wisconsin.gov, 608-266-2172

An adult emerald ash borer.

Photo: Leah Bauer, USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, Bugwood.org

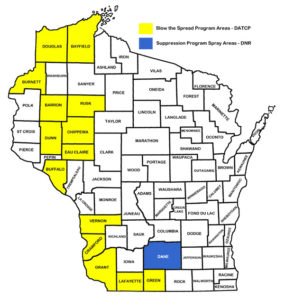

The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) enacted a statewide quarantine for the invasive insect emerald ash borer (EAB) on March 30, 2018. Previously, individual counties were quarantined when EAB was confirmed within each’s borders. Since EAB has been found in 48 of 72 Wisconsin counties, DATCP officials have determined that statewide regulation of the devastating ash tree pest is warranted.

Movement of ash wood, untreated ash products and hardwood firewood of any type to areas outside of Wisconsin will continue to be regulated by USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Plant Protection and Quarantine. (APHIS PPQ).

Within the state, Wisconsin businesses and members of the public will be able to freely move ash wood, ash products, and hardwood firewood to or from any Wisconsin county. Firewood restrictions will remain in effect on state and federal lands.

Items affected by the statewide EAB quarantine include ash wood with bark attached, larger ash wood chips, and hardwood firewood of any kind. County-by-county quarantines for gypsy moth, another invasive forest pest, remain in effect.

The move to a statewide quarantine does not mean that the state has given up on managing EAB; it is simply a shift in strategy as EAB continues its slow spread through the state. The Wisconsin DNR will continue releasing tiny, stingless wasps -natural enemies of EAB – at appropriate sites, which it has done since 2011. The DNR also continues participation in silvicultural trials in which different ash management strategies are being tested.

Most importantly, campers, tourists, and other members of the public are strongly encouraged to continue taking care when moving firewood within the state. “The actions taken by the Wisconsin public during the last few years have significantly slowed the spread of emerald ash borer and other invasive forest pests in the state,” said Wisconsin DNR EAB program manager Andrea Diss-Torrance. “We can continue to protect the numerous areas within our state that are not yet infested – including those in our own backyards – from tree-killing pests and diseases by following precautions.” Public members should continue to obtain firewood near campgrounds or cabins where they intend to burn it, or buy firewood that bears the DATCP-certified mark, meaning it has been properly seasoned or heat-treated to kill pests.

Emerald ash borer is native to China and probably entered the United States on packing material, showing up first in Michigan in 2002. It was first found in eastern Wisconsin in 2008.

For further information on EAB in Wisconsin, visit https://dnr.wi.gov/ using key words “emerald ash borer.”