Jack pine budworm caterpillar on jack pine. Photo: Todd Lanigan, WI DNR

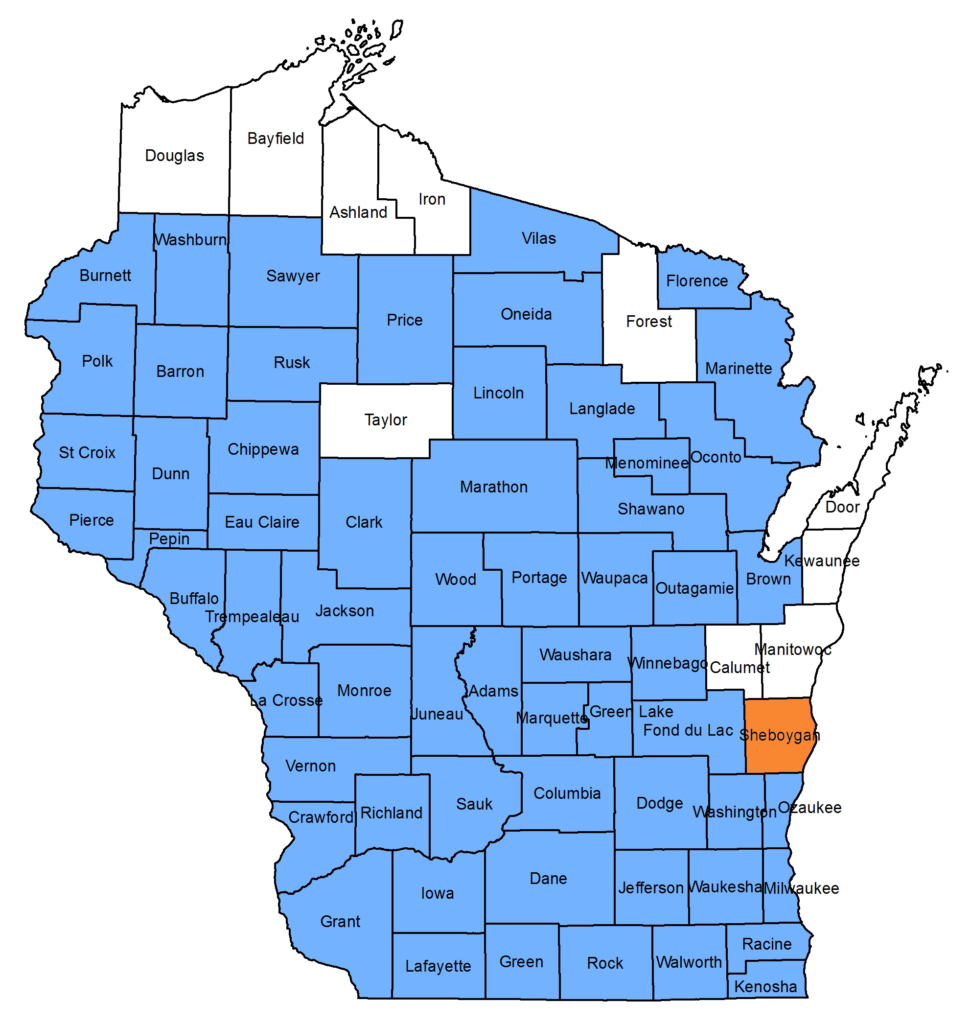

I conducted surveys for jack pine budworm caterpillars and egg masses in Dunn, Eau Claire, Jackson, Monroe, Pierce, and St. Croix counties last spring (caterpillars) and this fall (egg masses). Fortunately, I did not find any caterpillars and only one egg mass on red pine in Pierce County. Based on information from these surveys, jack pine budworm should not be a problem in 2018.

Jack pine budworm egg mass on jack pine needle. Photo: Todd Lanigan, WI DNR

In Wisconsin, jack pine budworm is a pest of jack, red, and white pine. It has rarely been found on white spruce, and in those cases only when the trees were located next to an infested plantation. Jack pine budworm can cause problems in natural stands, plantations, edge plantings/aesthetic strips, yard trees, and anywhere host trees are found.

For more information on management of jack pine in the state, click here.

Written by Todd Lanigan, forest health specialist, Eau Claire. Todd.Lanigan@wisconsin.gov; 715-839-1632