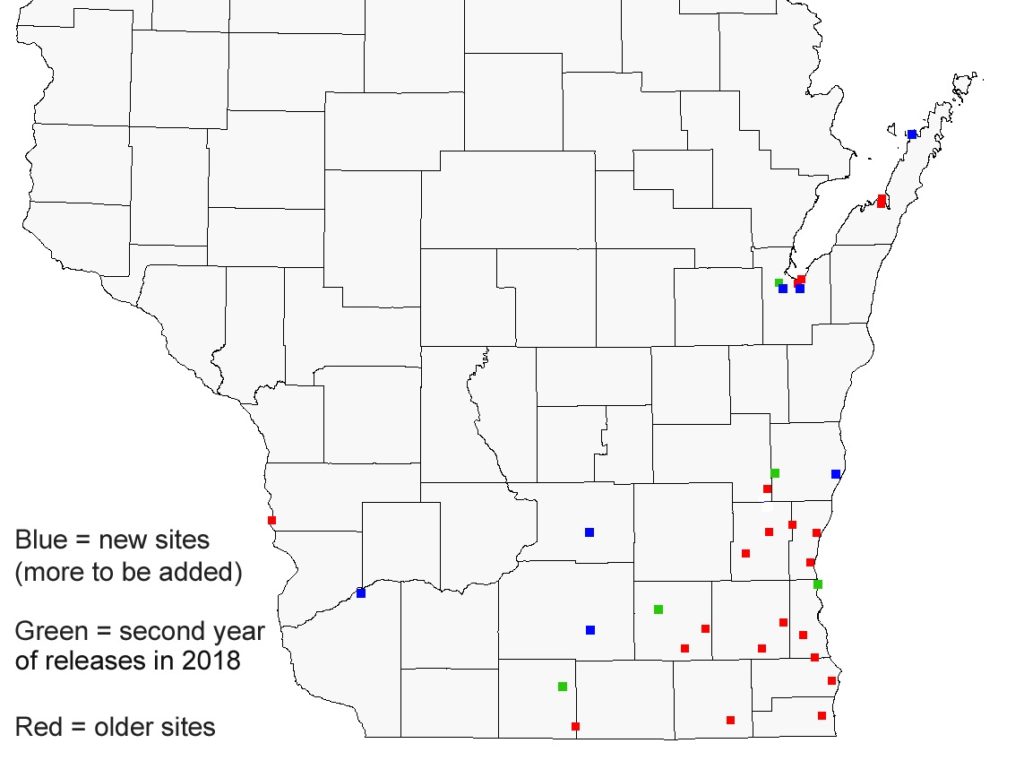

By Linda Williams, forest health specialist (Woodruff). Linda.Williams@wisconsin.gov; 715-356-5211, x232

During winter and early spring, damage to trees caused by porcupines and squirrels is evident in some areas. As spring arrives, new green leaves will mask the destruction.

This red pine had the bark stripped off it by a porcupine, which has wider incisors than a squirrel.

Porcupine and squirrels feed on the bark of trees, stripping it from branches and main stems. Stripping bark can girdle trees, resulting in branch dieback which shows up the year following the damage. If the branch isn’t completely girdled, it will start to grow callus tissue over damaged areas in an attempt to recover.

This maple bark was eaten by a squirrel. You can see where the tiny incisors scraped the bark down to the wood.

Both porcupines and squirrels feed on bark in the crowns of trees, so how can you tell which one is doing the damage if you don’t catch them in the act? The size of the teeth marks left in the wood is one clue. A gray squirrel’s incisors leave marks between 1.3 to 1.7 mm wide, while a porcupine’s teeth marks are nearly triple that, from 3.6 to 4.8 mm wide. You should also consider the species of tree being debarked: squirrels prefer maples while porcupines will feed on oak, pine, maple, and even spruce, as well as other species.

Rabbits, mice, and voles can cause similar damage to that caused by squirrels and porcupines, but damage will be located near the base of the tree instead of in the crown.

Another type of tree damage seen in late spring is when squirrels clip 4 to 6 inches off the tips of spruce branches, apparently to consume tasty buds. They drop the remainder of the branches to the forest floor, leaving a carpet of branch tips under spruce trees. I have yet to observe squirrels doing this, but the carpet of branch tips they leave prompts calls from concerned landowners each spring.

Spruce branch tips litter the ground where squirrels dropped them after clipping them from the tree. Although it can look alarming it rarely does enough damage to affect the overall health of the tree.

UW Extension offers a brochure about squirrels, including control options to share with landowners having trouble with these critters.